MLK in Waltham: “The Presence of Justice”

In 1957, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Waltham to give a talk at Brandeis as part of a series of interfaith seminars. He was 28 and already well-known nationally for his leadership in the Montgomery bus boycott, during which his house had been bombed several times.

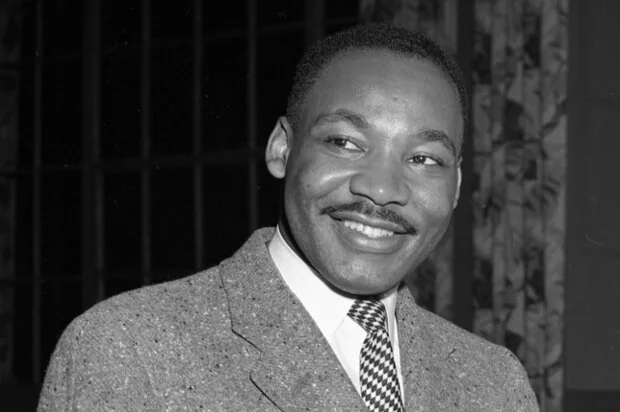

Dr. King at Brandeis in 1957. Image: Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University

In his talk, King acknowledged that the US was in the midst of “a real crisis in the area of race relations,” noting the resurgence of the KKK and rise of “White Citizens' Councils.” He explained that since the Civil War, African Americans had been made to feel that they were less than human:

“This is always a tragedy of physical slavery. It always ends up in the paralysis of mental slavery. And so long as the Negro accepted this place assigned to him, so long as he thought of himself in inferior terms, a sort of racial peace existed, but it was an uneasy peace. It was a negative peace. For you see, true peace is not merely the absence of some negative force. It is the presence of some positive force. Peace is not merely the absence of tension. It is the presence of justice, and the peace that existed at that time was a negative peace, an obnoxious peace, devoid of any positive meaning.”

King attributed the growth of the Civil Rights movement not to specific leaders or groups, but to a generation of African Americas learning to see themselves in a new way:

“With this new evaluation, with this new self respect, the negative peace of the nation and of the South was gradually undermined. The tension which we witness in the South land today can be explained in part by the revolutionary change in the Negro's evaluation of his nature and destiny and his determination to struggle and sacrifice and suffer until the sagging walls of segregation have finally been crushed by the battering rams of surging justice. This is the meaning of the crisis.”

King would speak at Brandeis once more, in 1963, the same year he led the march on Washington. His death in 1968 led to an extended period of protest throughout the country, including college campuses.

Dr. King meets with students at Brandeis. Photo: Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University

In early 1969, Black students at Brandeis occupied an administrative building called Ford Hall and refused to leave until a list of ten demands were met, having to do with Black representation and leadership on campus. Although there was no violence, the university president refused to negotiate with them because he considered this an inappropriate form of protest, and the students were described in media as “militants”. Though they ended up leaving the building after 11 days without any clear concessions from the administration, the incident led to changes including the creation of the Department of African and African American Studies and the MLK Fellowships at Brandeis.

In 1983, King’s birthday became a national holiday. King became a new kind of national hero-- not a president or military leader, but a leader of a nonviolent movement for social justice. But the world he died for has not arrived.

Too often, MLK Day is a day for performative activities that celebrate past progress without acknowledging ongoing problems that require year-round action to solve. That’s part of the reason WBFF has organized action hours, neighborhood clean-ups, and other activities throughout the year, not just in response to crises or a holiday.

Too often, MLK Day has been a celebration of the belief that racism is gradually disappearing, or has already disappeared. King’s “I Have A Dream” speech is distorted by those who believe we can create a “colorblind” society by simply not talking about race. In fact, Dr. King believed major structural change would be necessary to bring about true racial equality, and spoke about racism, poverty, and war as interrelated problems. This is part of the reason that WBFF supports efforts to address both racial and economic injustice in Waltham.

MLK Day can be a day to celebrate the contributions of one great African American while ignoring countless others. It can be a day to celebrate the fact that our country produced a leader who inspired movements for justice around the world, while forgetting that our own law enforcement agencies saw him as a dangerous radical, and that he was killed before his fortieth birthday, after many attempts on his life by his fellow Americans.

King’s advocacy of nonviolence is one of the most celebrated parts of his legacy, but also one of the most misunderstood. Recently we have seen Dr. King’s image and words twisted by those criticizing the Black Lives Matter movement for engaging in forms of protest they consider inappropriate. When protestors express anger they are criticized for not being “civil,” and incivility is conflated with violence, with the implication that Dr. King would not approve. Some have used pictures of King and other civil rights leaders dressed in Sunday clothes, linking arms and marching in dignified protest, to imply that the Civil Rights movement was successful because of its civility. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Meme comparing images of a Civil Rights protest in Selma, Alabama in 1965, and the police response.

Those protests were intended to be nonviolent but they were not intended to be civil. What we don’t see in those pictures is that dignified protests were met with brutal violence from law enforcement, and that is exactly what the organizers expected. They put themselves in harm’s way, without fighting back, to force the nation to see that segregation was based on violence. The mayhem that followed the police violence often included looting and vandalism in the area. Those who opposed the movement could choose to label the event a riot and place all the blame for the violence on the protestors. In recent years, we have seen a nearly identical pattern play out in response to BLM protests.

As President Biden takes office, we will likely be hearing more about civility from those who believe the best way to move beyond the contentious Trump era is to return to what Dr. King would call a “negative peace.” As we seek accountability for the recent attempted coup, we will likely hear many false equivalencies between the violent attack on our Capitol and BLM protests.

The Trump era has made it clear that racism is not going away on its own, and even with Trump out of office it remains a crisis. Though we don’t have Dr. King to lead us, we have his words to remind us that a crisis may be a necessary transition from a state of a negative peace to a state of true justice-- not the absence of something negative, but the presence of something positive.

Learn more about Dr. King’s Visit to Brandeis, and hear/read his full talk

Learn more about the Brandeis 1969 Ford Hall Occupation

Help us honor Dr. King’s true legacy year-round by taking action for racial and economic justice in our community.

Dr. King speaks with students at Brandeis. Photo: Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University